Why it Matters: Are Long Bond Yields a Canary in the Coal Mine?

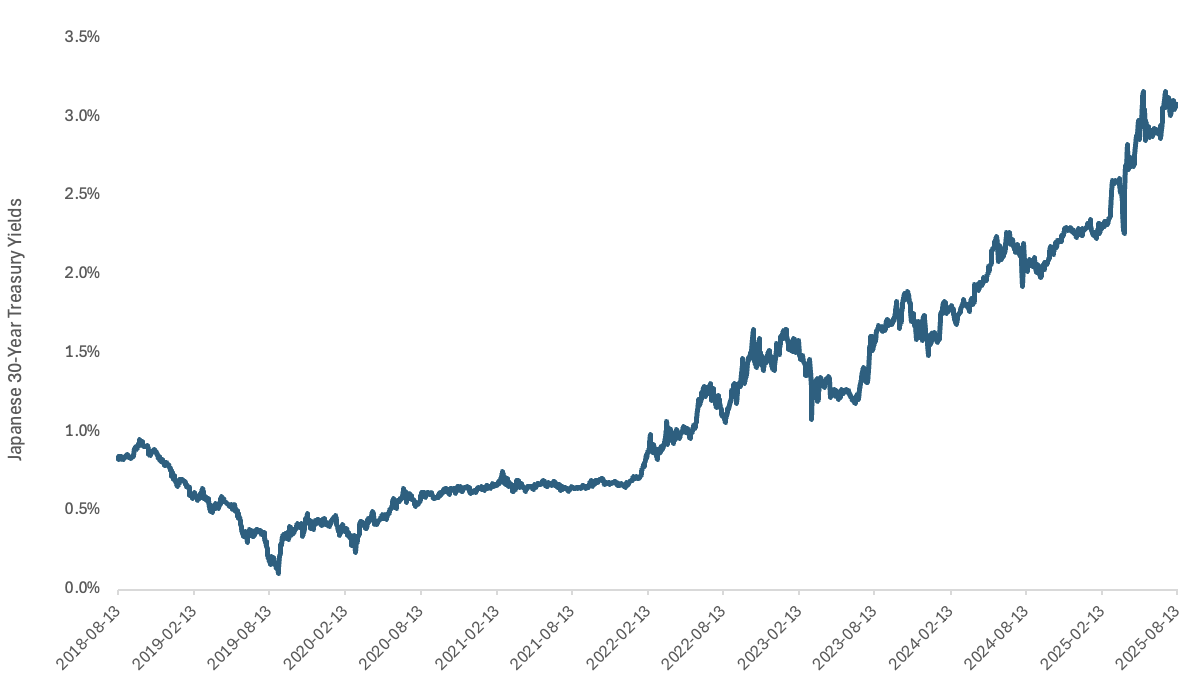

Since bottoming at just 0.1% in 2019, Japan’s 30-year bond yield recently surged above 3.0% — a dramatic shift for a country that pioneered non-conventional monetary policy. While the unwinding of yield curve control (YCC) played a role in this move, the real drivers are deeper: Decades of balance sheet expansion and the structural drag of an aging population. More concerning is what this may signal for the U.S. — a potential foreshadowing of what happens when high debt, rising rates, and demographic headwinds converge.

Japanese Long-Bond Yields have Surged!

Why it Matters for Investors…

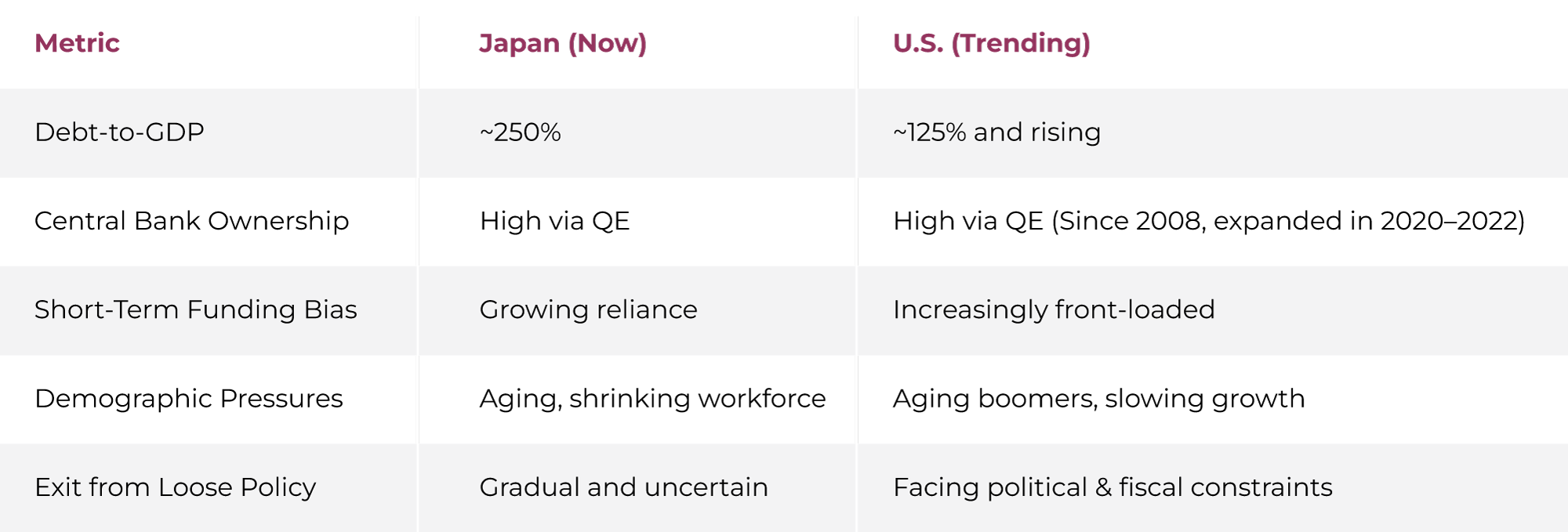

Japan’s situation isn’t an outlier — it’s a preview of what happens when central bank limits are tested and high debt loads clash with persistent inflation pressures.

Drawing Comparisons to the U.S.

While the U.S. dollar still benefits from reserve status and structural demand, the similarities are hard to ignore:

🏦 Powell’s Dilemma

As outlined in our latest Playbook iQ, Jerome Powell — Chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve — faces a no-win scenario:

He can either:

Cut rates to reduce refinancing costs, but risk reigniting inflation and undermining the Fed’s credibility,

or

Keep policy tight to preserve price stability but drive-up borrowing costs and stress public finances.

Either path leads to the same outcome: Higher refinancing costs — whether via rising debt levels or higher interest coupons.

The Trump administration appears to favour the short-term fix: lowering rates to ease government funding pressures. Powell, in contrast, is focused on defending the independence and long-term credibility of the Fed, a cornerstone of monetary stability that, once lost, is difficult to recover.

Replacing Powell with a dovish appointee or political loyalist risks a loss of market confidence, unanchoring inflation expectations and weakening the central bank’s grip on monetary conditions. Once the perception of independence is gone, markets demand more yield for the same bonds, not less.

The best way to ensure long-term fiscal sustainability is to defend the Fed’s independence, even if that means enduring tighter conditions in the short run

⏳ The Risk of Short-Term Funding

Relying too heavily on short-term issuance may seem efficient today — but it creates rollover risk tomorrow. If investors begin to question the U.S.’s fiscal discipline or inflation credibility, long-end yields can surge as markets demand a higher term premium to account for future uncertainty. Once control of the long end is lost, regaining it becomes exponentially more difficult, especially in a high-debt, politically polarized environment where fiscal discipline is already under scrutiny.

📌 Investors, Take Note…

While bearish sentiment has grown over the past decade, the path forward is far from certain. If currencies continue to debase, stocks and real assets may outperform in nominal terms, even as underlying fundamentals remain strained. At the same time, rising systemic stress underscores the importance of true safe havens.

What’s increasingly clear is this:

🎯 Fixed Income Alone Is No Longer a Reliable Portfolio Ballast

• Inflation steadily erodes the real value of future bond payments, weakening their role as a safe haven.

• Central banks may not cut in a crisis anymore — if inflation persists, the response could be tighter, not looser, monetary policy.

• Being a bear ISN’T the answer. Currency debasement can inflate asset prices, even as fundamentals deteriorate.

The answer isn’t fear — it’s robust portfolio construction that’s built to thrive across regimes.

The traditional 60/40 portfolio isn’t necessarily dead, but it is outdated in today’s more volatile, multi-regime environment. That’s why institutional investors — from pensions to endowments — are turning to private assets and alternative strategies to build more resilient portfolios.

At Q-Wealth, we’re bringing that institutional mindset to individual investors, with purpose-built portfolios designed to withstand a wider range of economic outcomes — not just one.